FULL POEM - SCROLL DOWN FOR LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

STANZA 1

England in 1819

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

The poem begins in media res as Shelley plunges the reader into the poem’s calamitous setting of ‘England in 1819’. This abrupt introduction emphasises the dire state of King and Country, intensifying the scornful narrative that ensues. The ‘dying King’ is the first point of focus, fitting with him being the country’s figurehead, and refers to King George III whose reign spanned from 1760 until his death in 1820, just one year after the poem’s creation. The narrator labels George as ‘mad’ referring to how he became permanently insane following the death of his daughter Princess Amelia in 1810, from which point his son, George IV, acted as Prince Regent until his father’s death.

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn,—mud from a muddy spring;

The narrator goes on to express their resentment for the country’s Princes, the criticism of which extends to the upper classes as a whole whose extravagant lifestyles juxtapose the widespread poverty prevalent across Britain at the time. ‘Dregs of their dull race’ expresses contempt for the line of royalty in power, the Hanoverians, that included the 15 children of George III, known for their lavish lifesytles, particularly the controversial eldest son, George IV. ‘Flow’ and ‘muddy spring’ form a lexical field of river-related imagery that likens the unrelenting hatred the public holds towards the royal family to the continual flow of water.

Rulers who neither see nor feel nor know,

But leechlike to their fainting country cling

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

The triplet, ‘neither see nor feel nor know’ is sensory language emphasising the disconnect between the nation’s ‘rulers’ and its people. Their lack of such attributes dehumanises them, linking to the narrator’s subsequent portrayal of them as ‘leechlike’, feeding off and consequently draining the country’s wealth. Herein, Shelley flips social hierarchy on its head, describing royalty and the upper classes as subhuman and sustained by the productivity of the working classes. Shelley orchestrates a symmetry between the first and third of the lines analysed here – between the triplets ‘neither see nor feel nor know’ and ’till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow’, tied together by the concluding rhymes. The plosive alliteration of ‘blind’, ‘blood’ and ‘blow’ in this third line gives it a harsh, aggressive sound when spoken that reflects the callous nature of the upper classes.

A people starved and stabbed in th’ untilled field;

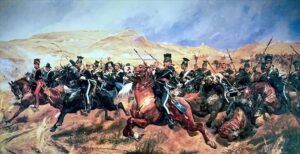

This line references the so-called Peterloo Massacre that took place in August 1819 – the atrocity of which is cited as the motivation behind Shelley’s scathing ‘England in 1819’. Eighteen people were killed in the massacre when a cavalry summoned by local magistrates charged into a crowd of 60,000 protesters peacefully demanding the reform of parliamentary representation. The ‘untilled field’ Shelley specifies refers to the site of the massacre, St Peter’s Field in Manchester. Despite the reader’s contextual inference of the Massacre, it is never explicitly mentioned as Shelley leaves the meaning of the line open to metaphorical interpretation such is the nationwide mistreatment (or metaphorical massacre) of the British working class.

An army, whom liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield;

‘Liberticide’, meaning the destruction of liberty, and ‘prey’ again refer, albeit not exclusively, to the aforementioned Peterloo Massacre in which the army preyed on the British public by killing innocent civilians protesting for the liberating human right of suffrage. Interestingly, the narrator describes the army as a ‘two-edged sword’ to the Crown that controlled it, alluding to the vulnerability of those in power to a military coup d’état, upon their overreliance on an army that has grown too powerful for them to control.

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

The British legal system has the opposite of its intended effect to enforce justice and order, instead tempting the population away from morality, leading to murder amongst other criminal activities. This leaves blood on the hands of the legal system and those who enforce it – captured by the double entendre, ‘sanguine’, meaning both bullish and optimistic as well as describing a blood-red colour. This can be viewed as a sort of naive, unfounded optimism of the enforceability of the laws that they fail to live up to which links to the word choice ‘golden’ that almost mocks the legal system’s lack of success and prestige that the colour would ordinarily symbolise. The colour’s connotations of wealth also feeds into the notion of the legal system benefitting the rich and subsequently bolstering the wealth inequality prevalent in England in 1819.

Religion Christless, Godless—a book sealed;

A senate, Time’s worst statute, unrepealed—

Well known for openly resenting religion, here Shelley doesn’t target Christianity specifically but rather the failings of the Church, resulting in a ‘Christless’ society, unable to live by the principles of a bible ‘sealed’ away from them. The term ‘Godless’ especially, connotes the societal abandonment of hope. The omnipotence of the ‘senate’, or parliament, is such that it is ‘unrepealed’, meaning those in power or the laws they pass cannot be challenged. The country was clearly devoid of democracy, with elections in Britain neither fair nor representative at the time – the situation improved slightly but remained far from fair following the 1832 Great Reform Act. The metaphor ‘Time’s worst statue’, therefore, figuratively describes the immovability of those in political power at the time.

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day.

The final couplet presents a seismic shift, or volta, from the sonnet’s scathing tone to leave a concluding, lasting message of hope and rebirth. The ‘graves’ mentioned are both a tribute to those lost in the Peterloo Massacre as well as a metaphor for the widespread mistreatment and injustice inflicted on the British people. Shelley foreshadows an uprising, akin to the French Revolution, symbolised by ‘the glorious phantom’ that willl ‘illumine’ the ‘tempestuous day’ and put an end to the nation’s suffering. The caesura following the word ‘burst’ in the final line creates a pause that reflects the calm following a storm which, in this case, Shelley predicts, and almost invites, to be revolutionary conflict. It’s evident the country has hit rock bottom and requires drastic measures to strive towards a brighter future.