FULL POEM - SCROLL DOWN FOR LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

Plane moves. I don’t like the feel of it.

In a car I’d suspect low tyre pressure.

A sudden swiftness, earth slithers

Off at an angle. The experienced solidly

This is rather a short hop for me

Read Guardians, discuss secretaries,

Business lunches. I crane for the last of dear

I’m doing it just to say I’ve done it

Familiar England, motorways, reservoir,

Building sites. Nimble tiny-disc, a sun

Tell us when we get to water

Runs up the porthole and vanishes.

Under us the broad meringue kingdom

The next lot of water’ll be the Med

Of cumulus, bearing the crinkled tangerine stain

That light spreads on an evening sea at home.

You don’t need an overcoat, but

It’s the sort of place where you need

A pullover. Know what I mean?

We have come too high for history.

Where we are now deals only with tomorrow,

Confounds the forecasters, dismisses clocks.

My last trip was Beijing. Know where that is?

Beijing. Peking, you’d say. Three weeks there, I was.

Peking is wrong. If you’ve been there

You call it Beijing, like me. Go on, say it.

Mackerel wigs dispense the justice of air.

At this height nothing lives. Too cold. Too near the sun.

LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

STANZA 1

Plane moves. I don’t like the feel of it.

In a car I’d suspect low tyre pressure.

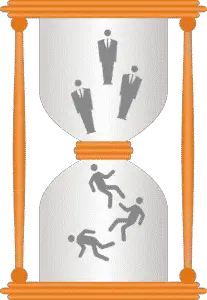

The poem consists of a back-and-forth narrative between two speakers (words of the second speaker will be in italics) with distinctly different outlooks on flying and the world in general. The first speaker is uneasy and nervous about flying, not liking the ‘feel of’ the plane and comparing the sensation to driving a car with ‘low tyre pressure’ (spongy and unstable).

STANZA 2

A sudden swiftness, earth slithers

Off at an angle. The experienced solidly

The sibilance (alliterative s’s) creates a rapid-fire, runaway tone to convey the first speaker’s overwhelmed feelings as the plane suddenly lifts off over which they hold no control. The use of the word ‘slithers’ is unsettling, referencing snakes which are a sinister symbol in literature. Again, this portrays the anxiety of the first speaker.

STANZA 3

This is rather a short hop for me

The second speaker interrupts the first (shown by the enjambement at the end of the previous stanza, demonstrating that the first speaker intended to continue speaking but was cut off). They evidently have experience of flying (this being a rather ‘short hop’ for them) and are consequently not phased by the experience. They are braggadocios about their calmness and respond to the first speaker with a very condescending tone.

STANZA 4

Read Guardians, discuss secretaries,

Business lunches. I crane for the last of dear

The first speaker lists a triplet of business-related activities, describing their perception of the lives of business people, of which the second speaker is most likely one, with whom they associate regular flying. Their work-driven existence juxtaposes the first speakers who cranes their neck to observe ‘dear familiar England’ as it disappears from sight.

STANZA 5

I’m doing it just to say I’ve done it

The second speaker is nonchalant and unconcerned regarding the flight – viewing it as a practicality (rooted in the fact that it is likely work-orientated), contrasting with the first speaker to whom the experience is groundbreaking and overwhelming.

STANZA 6

Familiar England, motorways, reservoir,

Building sites. Nimble tiny-disc, a sun

The first speaker continues from the fourth stanza, describing ‘dear familiar England’ that they craned their neck to see. The triplet of ‘motorways, reservoir, building sites’ is the focus of the first speaker’s flight (clinging to familiarity for comfort), which juxtaposes the focus of the second speaker’s flight of reading guardians, discussing secretaries and business lunches. This illustrates not only their differing outlooks on flying but also on life in general, namely the extent to which it is driven by work.

STANZA 7

Tell us when we get to water

Again the second speaker doesn’t care, finding it irrelevant. The reader gets the impression that they view their time to be too important to be taken up by the ramblings of the first speaker.

STANZA 8

Runs up the porthole and vanishes.

Under us the broad meringue kingdom

The ‘broad meringue kingdom of cumulus’ is a metaphor for the majestic expanse of clouds beneath the plane, its magnificence captured by the word ‘kingdom’, implying that the clouds exhibit a magical or spiritual quality. ‘Meringue’ symbolises the clouds’ softness and fluffiness, comforting the speaker and easing their fears of flight.

STANZA 9

The next lot of water’ll be the Med

The second speaker is looking ahead, keen to finish the journey. Again, their outlook is practical – viewing air travel solely as a tool to get from A to B, for which the Mediterranean Sea acts as a milestone. This contrasts with the first speaker who, less consumed by anxiety, romanticises the vistas of their surroundings.

STANZA 10

Of cumulus, bearing the crinkled tangerine stain

That light spreads on an evening sea at home.

‘The crinkled tangerine stain that light spreads on an evening sea at home’ is another striking and resplendent image created by the first speaker to illustrate the sun setting on the ‘evening sea’. The ‘tangerine’ signifies the rich, orange setting sun that glitters on ‘an evening sea at home’.

STANZA 11

You don’t need an overcoat, but

It’s the sort of place where you need

A pullover. Know what I mean?

To the idyllic imagery expressed by the first speaker, the second responds by talking about the mundane practicalities of travelling in the form of clothing suitability. It really does portray them as a rather lifeless individual which contrasts with the characterful, imaginative first speaker.

STANZA 12

We have come too high for history.

‘Too high for history’ literally refers to the altitude of the plane in which they fly, which defies what was though possible historically, as well as referring to modern society metaphorically.

Where we are now deal only with tomorrow,

Confounds the forecasters, dismisses clocks.

The speaker describes the development and advancements made by modern society as being so large so as to come at the expense of spontaneity and living in the moment. They remark that people ‘now deal only with tomorrow’, focussing too much on the future at the expense of happiness in the present.

STANZA 13

My last trip was Beijing. Know where that is?

Beijing. Peking, you’d say. Three weeks there, I was.

Peking is wrong. If you’ve been there

You call it Beijing, like me. Go on, say it.

The second speaker references the name change of China’s sprawling capital from Peking to Beijing (which took place on a national scale in 1958 and on an international scale in 1979) in their usual condescending, know-it-all tone (effectively addressing the first speaker as their inferior); claiming their superiority over the first speaker who they claim would only know it by its former name, Peking. The second speaker, however, gloats that, having been there, they are sufficiently educated and well-travelled to know the city by its correct name.

STANZA 14

Mackerel wigs dispense the justice of air.

This is another interesting, complex image composed by the first speaker – a welcome relief from the monotonous remarks of the second speaker. A ‘mackerel’ sky refers to a sky filled with rows of cirrocumulus or altocumulus clouds forming a rippling pattern resembling fish scales. Hence, the ‘mackerel wigs’ are a metaphor for these clouds which the speaker observes out of the window, which are described as removing ‘the justice’ from the ‘air’. The ‘wigs’ are an allusion to judges’ wigs, linking to the justice system and the ‘justice of air’. The whole line is a cunning interpretation of the phrase, ‘to cloud one’s judgement’, with the clouds being literal clouds which are clouding the ‘justice of air’ or its judgement.

At this height nothing lives. Too cold. Too near the sun.

The poem concludes with the oxymoron, ‘Too cold. Too near the sun’, which continues the metaphor from the 12th stanza. As human advancement continues to increase, and the ‘height’ of development rises, ‘nothing lives’ and it is ‘too cold’ – a metaphor for society losing compassion as it develops.