FULL POEM - SCROLL DOWN FOR LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

We are prepared: we build our houses squat,

Sink walls in rock and roof them with good slate.

This wizened earth has never troubled us

With hay, so, as you see, there are no stacks

Or stooks that can be lost. Nor are there trees

Which might prove company when it blows full

Blast: you know what I mean – leaves and branches

Can raise a tragic chorus in a gale

So that you listen to the thing you fear

Forgetting that it pummels your house too.

But there are no trees, no natural shelter.

You might think that the sea is company,

Exploding comfortably down on the cliffs

But no: when it begins, the flung spray hits

The very windows, spits like a tame cat

Turned savage. We just sit tight while wind dives

And strafes invisibly. Space is a salvo,

We are bombarded with the empty air.

Strange, it is a huge nothing that we fear.

SUMMARY AND CONTEXT

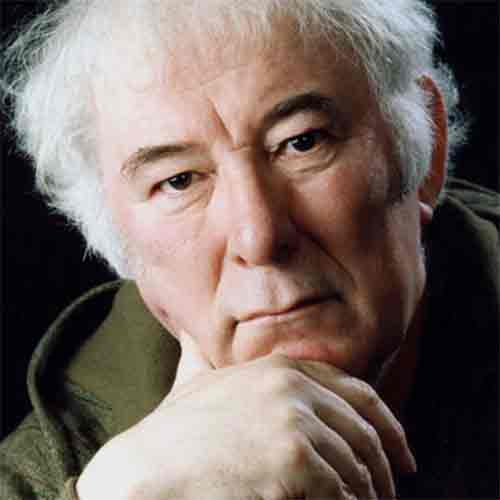

At first sight, the poem ‘Storm On The Island’ is quite literally about a storm on an island. It can, however, be interpreted as an extended metaphor for the political conflict in Northern Ireland taking place at the time of its publication in 1966 (notably the first eight letters of the title spell Stormont – the seat of the Northern Ireland Assembly). A 30 year period of conflict in Northern Ireland followed in the short aftermath of the poem’s release, known as ‘the Troubles’, during which Heaney was a prominent voice for peace, but avoided the role of political spokesmen throughout his work, hence the metaphorical meaning of ‘Storm on the Island’ is typical of his style.

LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

STANZA 1

We are prepared: we build our houses squat,

Sink walls in rock and roof them with good slate.

The poem is a monologue written in the first person – the personal pronoun ‘we’ immediately portraying a sense of togetherness within the community as well as serving to include the reader in the narrative, making them feel like they are part of it. Taken literally, the poem explores the conflict between mankind (the community) and nature (the storm) and the way in which the tone shifts throughout the poem is representative of how the community’s response changes as the storm endures. Initially in these opening lines the tone is defiant – the villagers are aware of the dangers posed by the storm but they are confident in their preparation, building their houses ‘squat’ (low to the ground) and with good, strong materials to help with stability in the storm. The strong, punchy sounding monosyllabic words in this second line reflect the strength of their houses.

This wizened earth has never troubled us

With hay, so, as you see, there are no stacks

Or stooks that can be lost. Nor are there trees

These lines describe how the barren ground is infertile and fails to provide the community with hay from which ‘stacks or stooks’ (piles of hay) can be formed. Heaney personifies the ground through the use of the word ‘wizened’ which is more commonly used to describe an elderly person, drawing a parallel between the infertility of the ground and that of an elderly woman – a rather sombre image that foreshadows the devastating consequences of the storm later in the poem.

Which might prove company when it blows full

The reader also learns that the area is devoid of surrounding trees which, if they existed, may ‘prove company’ for the villagers. Heaney uses personification here to create a sense of companionship and solidarity between the trees and the villagers and, with it, nature and mankind. This has the effect of showing that mankind is not always at odds with nature like it is with the storm. However, the lack of trees in this area serves to emphasise the community’s isolation on this remote island, resultantly heightening their vulnerability and, consequently, the tension and suspense of the narrative.

Blast: you know what I mean – leaves and branches

The word ‘blast’ is capitalised to add emphasis and, therefore, increase the power and abruptness of the plosive ‘b’ sound when spoken. The following caesura adds to its significance as well as mimicking the eery silence following a damaging storm. Metaphorically, the ‘blast’ of the storm could represent the gunshots or explosions heard during conflict. Although Northern Ireland was relativity stable and peaceful following the end of the IRA campaign in 1962 until the start of the Troubles in 1969, smaller scale politically influenced violence and terrorism persisted at the time of, and prior, to the poem’s writing in 1966 which Heaney may be obliquely referencing here.

Can raise a tragic chorus in a gale

So that you listen to the thing you fear

Forgetting that it pummels your house too.

But there are no trees, no natural shelter.

The racket made by trees in a storm is described as a ‘tragic chorus’. Here, the further personification of the trees, as well as how the word ‘tragic’ is an allusion to Greek tragedies, conveys the human-like suffering they experience throughout a storm – again a unity between the trees and mankind is present. However, as Heaney re-emphasises, ‘there are no trees, no natural shelter’ to protect the villagers.

You might think that the sea is company,

Exploding comfortably down on the cliffs

But no: when it begins, the flung spray hits

The very windows, spits like a tame cat

Turned savage. We just sit tight while wind dives

The imagery of the roaring ‘sea’ and the ‘cliffs’ introduced in these lines further emphasises the isolation of the villagers – the high cliffs cutting them off from civilisation. Whereas the trees were presented as potential companions, the opposite is true regarding the sea. The description of the sea as ‘exploding comfortably down on the cliffs’ is oxymoronic, portraying it as effortlessly powerful and intimidatingly so. The choice of the word ‘exploding’ is a further allusion to conflict and, taken metaphorically, the sea represents violence or terrorism and the island community its victims. The simile ‘spits like a tame cat turned savage’ symbolises how mankind has tried but failed to tame nature, in reality an impossible feat. Politically, this could be a metaphor for the various rebellions in Northern Ireland in the 1960s from people the government thought ‘tamed’ following the end of the IRA campaign.

And strafes invisibly. Space is a salvo,

We are bombarded with the empty air.

Strange, it is a huge nothing that we fear.

The symbols of military conflict continue in the final three lines – ‘strafes’ and ‘bombarded’ referencing dogfights such as those in the Second World War. The poem ends on a rather ambiguous note, with the narrator himself seemingly questioning the rationality of human fear, concluding that ‘it is a huge nothing’ that they’re afraid of. This oxymoron is a metaphor for the invisible yet deadly winds bombarding the island as well as, potentially, the way in which politics has indirectly led to the deaths of so many in Northern Ireland.