FULL POEM - SCROLL DOWN FOR LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

I run just one ov my daddy’s shops

from 9 o’clock to 9 o’clock

and he vunt me not to hav a break

but ven nobody in, I do di lock –

cos up di stairs is my newly bride

vee share in chapatti

vee share in di chutney

after vee hav made luv

like vee rowing through Putney –

Ven I return vid my pinnie untied

di shoppers always point and cry:

Hey Singh,ver yoo bin?

Yor lemons are limes

yor bananas are plantain,

dis dirty little floor need a little bit of mop

in di worst Indian shop

on di whole Indian road –

Above my head high heel tap di ground

as my vife on di web is playing wid di mouse

ven she netting two cat on her Sikh lover site

she book dem for di meat at di cheese ov her price –

my bride

she effing at my mum

in all di colours of Punjabi

den stumble like a drunk

making fun at my daddy

my bride

tiny eyes ov a gun

and di tummy ov a teddy

my bride

she hav a red crew cut

and she wear a Tartan sari

a donkey jacket and some pumps

on di squeak ov di girls dat are pinching my sweeties –

Ven I return from di tickle ov my bride

di shoppers always point and cry:

Hey Singh,ver yoo bin?

Di milk is out ov date

and di bread is alvays stale,

di tings yoo hav on offer yoo hav never got in stock

in di worst Indian shop

on di whole Indian road –

Late in di midnight hour

ven yoo shoppers are wrap up quiet

ven di precinct is concrete-cool

vee cum down whispering stairs

and sit on my silver stool,

from behind di chocolate bars

vee stare past di half-price window signs

at di beaches ov di UK in di brightey moon –

from di stool each night she say,

How much do yoo charge for dat moon baby?

from di stool each night I say,

Is half di cost ov yoo baby,

from di stool each night she say,

How much does dat come to baby?

from di stool each night I say,

Is priceless baby –

LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

I run just one ov my daddy’s shops

from 9 o’clock to 9 o’clock

and he vunt me not to hav a break

but ven nobody in, I do di lock –

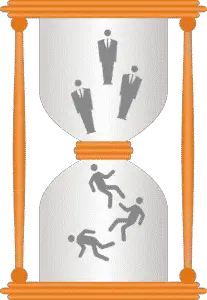

The tone of the poem is a humorous mix of English with a phonetic Punjabi accent. This humorous tone mirrors the witty pun ‘Singh Song’ that is the title, with the name ‘Singh’ being used by all baptized male Sikhs, which the poet Daljit Nagra is. In this opening stanza, the British Indian speaker introduces the reader to his life working in one of his father’s many corner shops. He paints a mundane picture of his working life and is seemingly lacking the appropriate independence of adulthood due to a controlling father. The caesura at the end of the fourth line creates a suspenseful pause in the poem’s rhythm which reflects the speaker’s feeling of excitement but nervousness as he disobeys his father’s instructions and closes the shop.

cos up di stairs is my newly bride

The speaker reveals that his newly-wed wife being upstairs is the reason why he was so eager to close the shop. The combination of the phonetic Punjabi accent and the broken English used throughout the poem (‘newly’ being an example) could be an allusion to the stereotype of a lack of English fluency in the British Indian community.

vee share in chapatti

vee share in di chutney

These two phrases are syntactic parallels that Nagra uses to emphasise the couple’s closeness.

after vee hav made luv

like vee rowing through Putney –

The simile ‘like vee rowing through Putney’ used to describe how the speaker and his wife have just made love is intended for comedic effect, adding to the humorous tone as well as capturing the passion present in the physical aspect of their relationship. ‘Putney’ is an affluent area in Greater London known as the starting point of the annual University Boat Race, hence acts as a symbol for quintessential British culture which contrasts with the speaker’s characteristically Indian lifestyle – namely the food that he eats and the corner shop where he works. This conveys how the speaker experiences conflicting cultures as a British Indian.

Ven I return vid my pinnie untied

This is the speaker’s equivalent of the ‘walk of shame’ – an image of romance-induced rebellion.

di shoppers always point and cry:

Hey Singh,ver yoo bin?

Di milk is out ov date

and di bread is alvays stale,

di tings yoo hav on offer yoo hav never got in stock

These hyperbolic complaints are the speaker’s perception of the shopper’s remarks (in reality they are unlikely to be this harsh). Perhaps, instead, it’s the voice of his father resonating in his head or just evidence of how much he hates his job.

in di worst Indian shop

on di whole Indian road –

Above my head high heel tap di ground

This line describes how the speaker’s wife wears high heels which symbolise the sexualisation of women in Western culture, which his wife, part of a new generation of Indian women, embraces.

as my vife on di web is playing wid di mouse

ven she netting two cat on her Sikh lover site

she book dem for di meat at di cheese ov her price –

Here, the speaker discusses how his wife runs a ‘Sikh lover site’ or dating agency for Sikhs. This is an extremely non-traditional job for an Indian woman, which links to how she has embraced Western culture. Furthermore, this modern approach to dating juxtaposes the tradition of arranged marriages in Indian culture.

my bride

she effing at my mum

in all di colours of Punjabi

den stumble like a drunk

making fun at my daddy

The speaker’s wife mocks and cusses his parents ‘in all di colours of Punjabi’ (using every swear word in the language) and the joyful, cheery tone suggests that he finds it hilarious rather than disrespectful. Their lack of respect for their elders is another example of their highly non-traditional outlook on life.

my bride

tiny eyes ov a gun

and di tummy ov a teddy

These two metaphors portray the speaker’s wife’s complex personality. The metaphor, ‘tiny eyes ov a gun’ portrays her fierce personality traits which links to how she insults the speaker’s parents in the previous stanza, whilst ‘di dummy ov a teddy’ portrays a softer, cuter side to her.

my bride

‘My bride’ is a refrain, it’s repetition suggesting the speaker’s infatuation with his wife. The use of the possessive pronoun ‘my’ demonstrates how proud he is that she’s his own and no one else’s. He’s possessive over his wife but in an endearing way.

she hav a red crew cut

and she wear a Tartan sari

a donkey jacket and some pumps

on di squeak ov di girls dat are pinching my sweeties –

The ‘red crew cut’, ‘donkey jacket’ and ‘some pumps’ are symbols of western culture, whilst her ‘tartan sari’ is a symbol of Indian culture. She embodies both cultures and, whilst her lifestyle is westernised in many ways, she remains proud of her Indian heritage.

Ven I return from di tickle ov my bride

The phrase ‘tickle ov my bride’ is another euphemism for the intimacy in their relationship, this time symbolising playfulness as opposed to the passion captured by the simile ‘like vee rowing through Putney’. Having both playfulness and passion shows just how good their relationship is and how much affection they have for each other.

di shoppers always point and cry:

Hey Singh,ver yoo bin?

Di milk is out ov date

and di bread is alvays stale,

di tings yoo hav on offer yoo hav never got in stock

This stanza follows the same structure as the third, emphasising how his skiving off work to spend time with his wife upstairs is a regular, repeated occurrence as is his customers’ outrage at this misconduct. The second triplet of their complaints on top of those from the third stanza, express just how terrible a shopkeeper he is, even failing to stock adequate bread and milk, two basic staples of the British diet.

in di worst Indian shop

on di whole Indian road –

These two lines are a refrain, repeated to demonstrate how he is actually quite proud of these remarks, treating the title of ‘worst Indian shop on di whole Indian road’ as an accolade rather than something to be ashamed of.

Late in di midnight hour

ven yoo shoppers are wrap up quiet

ven di precinct is concrete-cool

The stanza begins with the temporal marker, ‘late in di midnight hour’, which represents a change in tone from the activity of the daytime to the quieter, intimate nighttime setting when his customers are asleep and ‘wrap up quiet’. He directly addresses his customers in an evidently frustrated tone, ironic as his and his family’s livelihood is dependent on them.

vee cum down whispering stairs

and sit on my silver stool,

from behind di chocolate bars

vee stare past di half-price window signs

at di beaches ov di UK in di brightey moon –

Nagra includes romantic imagery in this stanza to reflect how the narrator feels the loving bond between him and his wife flourishes in the nighttime hours without the distraction of work and complaining customers. The ‘whispering stairs’, for example, is a magical, enchanting image symbolising secrecy – which we can infer is associated with sex. Whilst the description of the ‘silver stool’ and the beaches ‘in di brighter moon’ paint the, traditionally romantic, image of a moonlit setting that humorously juxtaposes the realities of the surrounding not so romantic ‘chocolate bars’ and ‘half-price window signs’.

from di stool each night she say,

How much do yoo charge for dat moon baby?

from di stool each night I say,

Is half di cost ov yoo baby,

from di stool each night she say,

How much does dat come to baby?

from di stool each night I say,

Is priceless baby –

The poem concludes with this dialogue of rhyming couplets between the couple – its repetitive and rhythmic nature reflecting the harmony and emotional connection between them. Its structure is also reminiscent of a simple love poem and it’s fitting that the poem ends on this note, with the speaker forgetting his work and his customers and instead focusing on what’s most important to him in life, his wife. It’s a heartfelt conclusion as the speaker declares that he charges half for the moon of what he does for her and even that is priceless, implying that her worth to him is beyond priceless – the moral of the poem, perhaps, that love is more important than money.