FULL POEM - SCROLL DOWN FOR LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

In his dark room he is finally alone

with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows.

The only light is red and softly glows,

as though this were a church and he

a priest preparing to intone a Mass.

Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.

He has a job to do. Solutions slop in trays

beneath his hands, which did not tremble then

though seem to now. Rural England. Home again

to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel,

to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet

of running children in a nightmare heat.

Something is happening. A stranger’s features

faintly start to twist before his eyes,

a half-formed ghost. He remembers the cries

of this man’s wife, how he sought approval

without words to do what someone must

and how the blood stained into foreign dust.

A hundred agonies in black and white

from which his editor will pick out five or six

for Sunday’s supplement. The reader’s eyeballs prick

with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers.

From the aeroplane he stares impassively at where

he earns his living and they do not care.

LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

STANZA 1

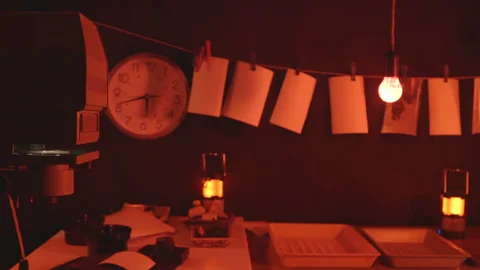

In his dark room he is finally alone

Duffy immediately creates a dark, somber tone by immediately setting the scene in the photographer’s ‘dark room’. A darkroom is used to process light-sensitive photographic film to develop photographs, hence would be how a photographer would publish their photos prior to the digital age. So here in a literal sense, the poem’s subject, the war photographer, is back home developing the photos he’s amassed from war. Figuratively, this tranquil setting juxtaposes the violence of the battlefields where he would have taken his photos, enabling a time for reflection – inevitably traumatic and depressing in nature for which the darkness is a metaphor.

with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows.

The photographer winds his photographic film into ‘speels of suffering’ – a metaphor that portrays the sheer brutality of war captured in his photos. The sibilance in this line further emphasises this, resulting in a sinister hissing sound when spoken which is onomatopoeic for the hissing of shells and bullets on a battlefield.

The only light is red and softly glows

as though this were a church and he

a priest preparing to intone a Mass.

Duffy compares the dark room to a church through the simile ‘as though this were a church’ and the photographer to a priest through the metaphor ‘and he a priest preparing to intone a Mass’. The imagery of the red light that ‘softly glows’ supports this comparison. Red light is the only light source present in dark rooms to prevent damage to the photographic film and the overexposure of photographs. Meanwhile, in a church, it is also normally the colour of a sanctuary or altar lamp in the Christian tradition. The way in which the photographer prepares the photos of the victims is ritualistic, akin to a priest conducting a funeral. However, unlike how a priest is preparing to lay the dead to rest, the photographer is preparing for them to be published in newspapers – a contrast that makes the reader question the humanity of his profession.

Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.

The list of places of conflict, ‘Belfast.Beirut.Penh’ that he has photographed is an example of asyndeton – a list without conjunctions that here is instead punctuated with full stops. Such caesura reflects the photographer’s troubled pause for reflection as he prepares photos from each setting and allows the reader to do the same. ‘All flesh is grass’ is a biblical reference, here signifying how fragile and temporary life is especially in times of conflict, perishing and replenishing just like grass with the seasons.

STANZA 2

He has a job to do. Solutions slop in trays

beneath his hands, which did not tremble then

though seem to now. Rural England. Home again

The abruptness of the opening to this stanza mirrors the photographer snapping back to reality and the job at hand, having become distracted pondering the trauma he has witnessed. Duffy also explores the irony between the photographer’s conduct when on the battlefield and when at home in ‘Rural England’. To work professionally at war, he must remain emotionally detached from his subjects, hence there’s a callous efficiency that the job entails. When at home though, a pause in the chaos of war results in the opportunity for its traumas to catch up with and consume him, leading to his hands trembling as he prepares the photographs even though they didn’t when he captured them.

to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel,

‘Ordinary pain’ is an oxymoron, emphasising the insignificance of the so-called ‘first-world problems’ experienced by those living in ‘Rural England’ compared to the problems of those living in ‘Belfast, Beirut, Phnom Penh’ and other war torn countries the photographer has worked in.

to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet

of running children in a nightmare heat.

This rhyming couplet that concludes this stanza captures the brutality of the conflicts that he is reflecting upon by referencing the heartbreaking ‘Napalm Girl’ photograph depicting nine-year old Phan Thi Kim Phúc fleeing from a South Vietnamese air strike in 1972.

STANZA 3

Something is happening. A stranger’s features

Duffy opens this third stanza abruptly with a short sentence, like the last. Here the effect is to create suspense as the caesura results in a pause in the narrative that leaves the reader hanging on what the ‘something’ that is happening actually is.

faintly start to twist before his eyes,

a half-formed ghost. He remembers the cries

The imagery used to describe the development of this particular photograph is animalistic – the use of the word ‘twist’ evokes the image of a wounded animal writhing in pain, used to capture the agony of the ‘half-formed ghost’ (a metaphor for the dying man that describes he’s closer to dying than living) in the photograph.

of this man’s wife, how he sought approval

without words to do what someone must

and how the blood stained into foreign dust.

These lines explore the morality of the photographer’s profession. A dying man lies on the ‘blood stained’ ground beneath him, whilst the man’s wife cries in desperation as she loses him. Meanwhile, the photographer is a passive spectator, unable to offer help to the man or his wife, instead, he’s more of an intruder in their last moments together. His motive isn’t to cure the suffering but photograph and document it and in the moment that seems selfish, as though he is using it for his own gain. This, in part, is true – the more vivid and poignant the suffering that he captures is, the more successful he and his work become. But on the flip side, these are stories that need to be told, people at home, politicians, need to be made aware of these devastating conflicts if they’re ever going to end and the photographer is putting himself in the firing line to document these stories and one could argue that you don’t get less selfish than that.

STANZA 4

A hundred agonies in black and white

from which his editor will pick out five or six

for Sunday’s supplement. The reader’s eyeballs prick

The final stanza describes the destination and purpose of the photographs that depict ‘a hundred agonies in black and white’. The term ‘a hundred agonies’ emphasises the scale of suffering that the photographer has captured and accumulated from country to country. ‘Five or six’ of the most shocking are then selected and published ‘for Sunday’s supplement’, designed to make as profound an impression on the reader as possible. As touched on previously, herein lies the debate on the morality of such publications.

with tears between the bath and pre-lunch beers.

From the aeroplane he stares impassively at where

he earns his living and they do not care.

Having considered those who were the subject of his photographs, the photographer shifts his attention to those consuming them, the people back home in England who enjoy a much safer and easier life in comparison. How their ‘eyeballs prick with tears’ connotes how they are moved briefly but not sincerely by the photographs, akin to the momentary feeling of pain of pricking one’s finger, which subsides quickly at the thought of ‘pre-lunch beers’. The internal rhyme between ‘tears’ and ‘beers’ lightens the tone – further emphasising the shallow, temporary impact the photographs have on the readers. The poem concludes with the photographer coming to this realisation about his audience as he travels by plane most likely to his next place of work and no doubt this leaves him questioning the purpose and morality of his profession as he prepares to do it all over again.